Years ago, when we were just graduating from college, Quinn and I had a choice: Washington, D.C., or New York? In Washington he’d been offered a fine, upstanding job as a legislative aide to a U.S. senator; he would wear suits every day and work in an office next to the Capitol building. In New York, he would have a gig designing textbooks for McGraw-Hill. The two roads diverged in a serious way. The pros/cons list we had to make to handle that moving decision were epic.

Eventually, we went with D.C. I can admit now, sixteen years later, that we did it primarily because it seemed safer and easier, in so many ways. My skewed vision of New York City revolved around crime, rats, steaming subways, and soul-killing rent payments for squalid apartments. Frankly, the city scared the crap out of me.

Since then, I’ve visited Manhattan enough times to know that it’s not one nonstop episode of Law and Order: SVU. Last week, however, on a three-day trip to meet with my agent and editor, it felt for the first time like the city was pulling out all the stops to sway me into loving it (and to maybe give me a slight twinge of regret that I’ve never lived there).

The weather was insanely glorious. It was the first week of November and warm enough to shrug off jackets and sweaters. With the sense that this would be the season’s last hurrah, people were streaming out of their office buildings to luxuriate outdoors. I spent a good 45 minutes on a bench in Washington Square Park, people-watching and reading.

In fact, apart from a few meetings, the week’s to-do list went a little something like this:

In This Is Where You Belong I explain why walking helps us fall in love with where you live, so no shock it does that when we’re on vacation. This time, I never once set foot on the subway. Not only did I clock between 17,000 and 24,000 steps each day, thus enabling guilt-free pizza consumption, I never had that vertigo-inducing feeling of emerging onto a street corner and having no idea which way is north. By walking aimlessly through streets that weren’t exactly on the way to somewhere, I finally figured my way around a little bit.

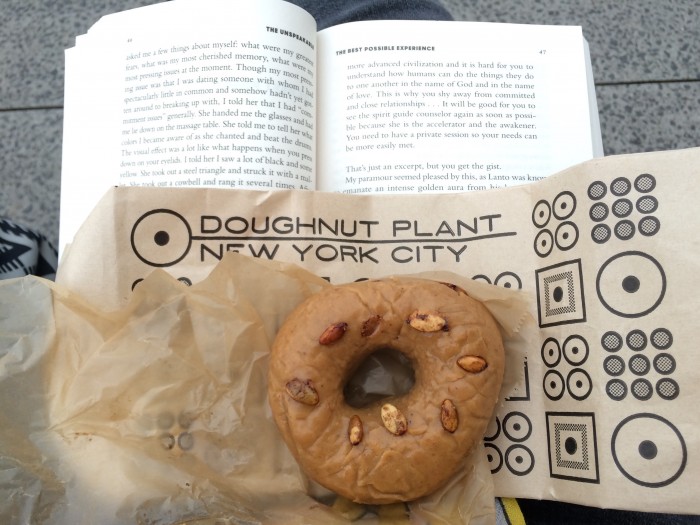

Travel gives us a sped-up, high-intensity version of the place attachment process. By doing only what made me happy, I designed precisely the kind of experience that would make me fall in love with New York—or any city, for that matter. At the end of the week, I found myself sitting on a bench on the High Line (obligatory stop for all New York tourists), reading a book of Meghan Daum essays I’d bought from the Strand and eating a pumpkin donut from Donut Plant. And I wouldn’t mind doing that most days of the week.

Like this post? Share it!