Image_Less_Ordinary/Flickr

Add this to the list of things you probably already know: Volunteering is good for you. Like, seriously good for you. Various studies have shown that spending as little as an hour a week volunteering can:

- Increase your well-being, making you more satisfied with everything about your life: your finances, your health, your accomplishments, your relationships. Basically it gives you a huge self-esteem boost.

- Help you feel more socially connected.

- Reduce depression and loneliness.

- Make you physically healthier.

- Send you a burst of dopamine, the feel-good hormone, to elevate your mood.

For a supposedly selfless behavior, volunteering offers a lot of selfish rewards. But here’s one that most people don’t think about: It can make you feel happier about the place where you live.

Why? For starters, look at that list above. You’re happier and healthier! And one of the main principles of loving where you live that I learned while researching my book This Is Where You Belong is this: When you’re happy and healthy, you also are happy and healthy where you are. Contentment about your life in general tends to spill over into contentment with your surroundings—the rose-colored glasses effect.

Volunteering also increases our social capital by connecting us with new people and boosting the breadth of your relationships. Since friendship is at the top of the list of qualities that make us want to stay in our towns, that can increase place attachment.

Of course, even with all these benefits, only about one in four Americans volunteers nationally. In some cities, like Miami, the figure gets as low as 14 percent. But the more passionately we feel about our town, or on a smaller scale, a particular location in our town (like a library or an art museum), the more likely we are to volunteer.

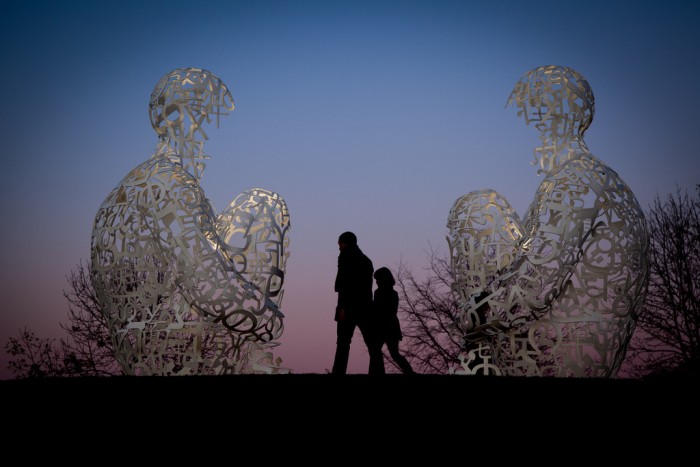

Consider a 2014 study about volunteers at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park in West Yorkshire, England. “Why do I volunteer?” said one woman. “It’s easy. Because I love the place. I love the park, I love the sculpture, the exhibitions which are put on.”

Another person explained how her sense of investment and connection increased as she volunteered there. “Working here made me experience more of the park . . . gradually getting to know it and feeling and understanding more of what it is about.”

One said that because she loved the park so much, she was eager for it to thrive. Motivated by a similar feeling, most volunteers turned into ambassadors for the park or advocates for it. They brought their own friends to visit, both to help the park’s finances and to encourage their friends to fall in love with it the way they had.

All this, concluded study author Saskia Warren, now a lecturer in human geography at the University of Manchester, indicated that “passion or love for a place can motivate volunteers.” And it matches up well with items from the place attachment scale in my book. When we’re very attached to the place where we live, we agree with statements like these:

- I like to tell people about where I live.

- I rely on where I live to do the stuff I care about most.

- I’m really interested in knowing what’s going on here.

- I feel loyal to this community.

- I care about the future success of this town.

When we care about what happens to our town, we step up. We want to fix problems, or help the parts we love become even more lovable. The more we do that, the more we identify with our town. Not surprisingly, volunteers tend to make cities do better as well. Our success and our town’s success are intertwined.

Sources:

Saskia Warren, “‘I Want This Place to Thrive’: Volunteering, Co-production and Creative Labour,” Area 46, no. 3 (2014): 278–84.

David Mellor et al., “Volunteering and Its Relationship with Personal and Neighborhood Well-Being,” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 38, no. 1 (February 2009): 144-159.